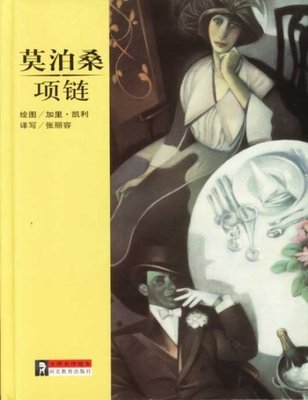

Guy deMaupassant

TheNecklace

She was one of thosepretty and charming girls born, as though fate had blundered overher, into a family of artisans. She had no marriage portion, noexpectations, no means of getting known, understood, loved, andwedded by a man of wealth and distinction; and she let herself bemarried off to a little clerk in the Ministry of Education. Hertastes were simple because she had never been able to afford anyother, but she was as unhappy as though she had married beneathher; for women have no caste or class, their beauty, grace, andcharm serving them for birth or family, their natural delicacy,their instinctive elegance, their nimbleness of wit, are their onlymark of rank, and put the slum girl on a level with the highestlady in the land.

Shesuffered endlessly, feeling herself born for every delicacy andluxury. She suffered from the poorness of her house, from its meanwalls, worn chairs, and ugly curtains. All these things, of whichother women of her class would not even have been aware, tormentedand insulted her. The sight of the little Breton girl who came todo the work in her little house aroused heart-broken regrets andhopeless dreams in her mind. She imagined silent antechambers,heavy with Oriental tapestries, lit by torches in lofty bronzesockets, with two tall footmen in knee-breeches sleeping in largearm-chairs, overcome by the heavy warmth of the stove. She imaginedvast saloons hung with antique silks, exquisite pieces of furnituresupporting priceless ornaments, and small, charming, perfumedrooms, created just for little parties of intimate friends, men whowere famous and sought after, whose homage roused every otherwoman's envious longings.

Whenshe sat down for dinner at the round table covered with athree-days-old cloth, opposite her husband, who took the cover offthe soup-tureen, exclaiming delightedly: "Aha! Scotch broth! Whatcould be better?" she imagined delicate meals, gleaming silver,tapestries peopling the walls with folk of a past age and strangebirds in faery forests; she imagined delicate food served inmarvellous dishes, murmured gallantries, listened to with aninscrutable smile as one trifled with the rosy flesh of trout orwings of asparagus chicken.

< 2 >

Shehad no clothes, no jewels, nothing. And these were the only thingsshe loved; she felt that she was made for them. She had longed soeagerly to charm, to be desired, to be wildly attractive and soughtafter.

Shehad a rich friend, an old school friend whom she refused to visit,because she suffered so keenly when she returned home. She wouldweep whole days, with grief, regret, despair, and misery.

*

One evening her husband came home with an exultant air, holding alarge envelope in his hand.

"Here'ssomething for you," he said.

Swiftlyshe tore the paper and drew out a printed card on which were thesewords:

"TheMinister of Education and Madame Ramponneau request the pleasure ofthe company of Monsieur and Madame Loisel at the Ministry on theevening of Monday, January the 18th."

Insteadof being delighted, as her husband hoped, she flung the invitationpetulantly across the table, murmuring:

"Whatdo you want me to do with this?"

"Why,darling, I thought you'd be pleased. You never go out, and this isa great occasion. I had tremendous trouble to get it. Every onewants one; it's very select, and very few go to the clerks. You'llsee all the really big people there."

Shelooked at him out of furious eyes, and said impatiently: "And whatdo you suppose I am to wear at such an affair?"

Hehad not thought about it; he stammered:

"Why,the dress you go to the theatre in. It looks very nice, to me . .."

Hestopped, stupefied and utterly at a loss when he saw that his wifewas beginning to cry. Two large tears ran slowly down from thecorners of her eyes towards the corners of her mouth.

< 3 >

"What'sthe matter with you? What's the matter with you?" hefaltered.

Butwith a violent effort she overcame her grief and replied in a calmvoice, wiping her wet cheeks:

"Nothing.Only I haven't a dress and so I can't go to this party. Give yourinvitation to some friend of yours whose wife will be turned outbetter than I shall."

Hewas heart-broken.

"Lookhere, Mathilde," he persisted. "What would be the cost of asuitable dress, which you could use on other occasions as well,something very simple?"

Shethought for several seconds, reckoning up prices and also wonderingfor how large a sum she could ask without bringing upon herself animmediate refusal and an exclamation of horror from thecareful-minded clerk.

Atlast she replied with some hesitation:

"Idon't know exactly, but I think I could do it on four hundredfrancs."

Hegrew slightly pale, for this was exactly the amount he had beensaving for a gun, intending to get a little shooting next summer onthe plain of Nanterre with some friends who went lark-shootingthere on Sundays.

Neverthelesshe said: "Very well. I'll give you four hundred francs. But try andget a really nice dress with the money."

Theday of the party drew near, and Madame Loisel seemed sad, uneasyand anxious. Her dress was ready, however. One evening her husbandsaid to her:

"What'sthe matter with you? You've been very odd for the last threedays."

"I'mutterly miserable at not having any jewels, not a single stone, towear," she replied. "I shall look absolutely no one. I would almostrather not go to the party."

< 4 >

"Wearflowers," he said. "They're very smart at this time of the year.For ten francs you could get two or three gorgeous roses."

Shewas not convinced.

"No. . . there's nothing so humiliating as looking poor in the middleof a lot of rich women."

"Howstupid you are!" exclaimed her husband. "Go and see MadameForestier and ask her to lend you some jewels. You know her quitewell enough for that."

Sheuttered a cry of delight.

"That'strue. I never thought of it."

Nextday she went to see her friend and told her her trouble.

MadameForestier went to her dressing-table, took up a large box, broughtit to Madame Loisel, opened it, and said:

"Choose,my dear."

Firstshe saw some bracelets, then a pearl necklace, then a Venetiancross in gold and gems, of exquisite workmanship. She tried theeffect of the jewels before the mirror, hesitating, unable to makeup her mind to leave them, to give them up. She kept onasking:

"Haven'tyou anything else?"

"Yes.Look for yourself. I don't know what you would like best."

Suddenlyshe discovered, in a black satin case, a superb diamond necklace;her heart began to beat covetously. Her hands trembled as shelifted it. She fastened it round her neck, upon her high dress, andremained in ecstasy at sight of herself.

Then,with hesitation, she asked in anguish:

"Couldyou lend me this, just this alone?"

"Yes,of course."

Sheflung herself on her friend's breast, embraced her frenziedly, ————andwent away with her treasure. The day of the party arrived. MadameLoisel was a success. She was the prettiest woman present, elegant,graceful, smiling, and quite above herself with happiness. All themen stared at her, inquired her name, and asked to be introduced toher. All the Under-Secretaries of State were eager to waltz withher. The Minister noticed her.

< 5 >

Shedanced madly, ecstatically, drunk with pleasure, with no thoughtfor anything, in the triumph of her beauty, in the pride of hersuccess, in a cloud of happiness made up of this universal homageand admiration, of the desires she had aroused, of the completenessof a victory so dear to her feminine heart.

Sheleft about four o'clock in the morning. Since midnight her husbandhad been dozing in a deserted little room, in company with threeother men whose wives were having a good time. He threw over hershoulders the garments he had brought for them to go home in,modest everyday clothes, whose poverty clashed with the beauty ofthe ball-dress. She was conscious of this and was anxious to hurryaway, so that she should not be noticed by the other women puttingon their costly furs.

Loiselrestrained her.

"Waita little. You'll catch cold in the open. I'm going to fetch acab."

Butshe did not listen to him and rapidly descended the staircase. Whenthey were out in the street they could not find a cab; they beganto look for one, shouting at the drivers whom they saw passing inthe distance.

Theywalked down towards the Seine, desperate and shivering. At lastthey found on the quay one of those old nightprowling carriageswhich are only to be seen in Paris after dark, as though they wereashamed of their shabbiness in the daylight.

Itbrought them to their door in the Rue des Martyrs, and sadly theywalked up to their own apartment. It was the end, for her. As forhim, he was thinking that he must be at the office at ten.

Shetook off the garments in which she had wrapped her shoulders, so asto see herself in all her glory before the mirror. But suddenly sheuttered a cry. The necklace was no longer round her neck!

< 6 >

"What'sthe matter with you?" asked her husband, already halfundressed.

Sheturned towards him in the utmost distress.

"I. . . I . . . I've no longer got Madame Forestier's necklace. . .."

Hestarted with astonishment.

"What!. . . Impossible!"

Theysearched in the folds of her dress, in the folds of the coat, inthe pockets, everywhere. They could not find it.

"Areyou sure that you still had it on when you came away from theball?" he asked.

"Yes,I touched it in the hall at the Ministry."

"Butif you had lost it in the street, we should have heard itfall."

"Yes.Probably we should. Did you take the number of the cab?"

"No.You didn't notice it, did you?"

"No."

Theystared at one another, dumbfounded. At last Loisel put on hisclothes again.

"I'llgo over all the ground we walked," he said, "and see if I can'tfind it."

Andhe went out. She remained in her evening clothes, lacking strengthto get into bed, huddled on a chair, without volition or power ofthought.

Herhusband returned about seven. He had found nothing.

Hewent to the police station, to the newspapers, to offer a reward,to the cab companies, everywhere that a ray of hope impelledhim.

Shewaited all day long, in the same state of bewilderment at thisfearful catastrophe.

Loiselcame home at night, his face lined and pale; he had discoverednothing.

< 7 >

"Youmust write to your friend," he said, "and tell her that you'vebroken the clasp of her necklace and are getting it mended. Thatwill give us time to look about us."

Shewrote at his dictation.

*

By the end of a week they had lost all hope.

Loisel,who had aged five years, declared:

"Wemust see about replacing the diamonds."

Nextday they took the box which had held the necklace and went to thejewellers whose name was inside. He consulted his books.

"Itwas not I who sold this necklace, Madame; I must have merelysupplied the clasp."

Thenthey went from jeweller to jeweller, searching for another necklacelike the first, consulting their memories, both ill with remorseand anguish of mind.

Ina shop at the Palais-Royal they found a string of diamonds whichseemed to them exactly like the one they were looking for. It wasworth forty thousand francs. They were allowed to have it forthirty-six thousand.

Theybegged the jeweller not to sell it for three days. And theyarranged matters on the understanding that it would be taken backfor thirty-four thousand francs, if the first one were found beforethe end of February.

Loiselpossessed eighteen thousand francs left to him by his father. Heintended to borrow the rest.

Hedid borrow it, getting a thousand from one man, five hundred fromanother, five louis here, three louis there. He gave notes of hand,entered into ruinous agreements, did business with usurers and thewhole tribe of money-lenders. He mortgaged the whole remainingyears of his existence, risked his signature without even knowingif he could honour it, and, appalled at the agonising face of thefuture, at the black misery about to fall upon him, at the prospectof every possible physical privation and moral torture, he went toget the new necklace and put down upon the jeweller's counterthirty-six thousand francs.

< 8 >

WhenMadame Loisel took back the necklace to Madame Forestier, thelatter said to her in a chilly voice:

"Youought to have brought it back sooner; I might have neededit."

Shedid not, as her friend had feared, open the case. If she hadnoticed the substitution, what would she have thought? What wouldshe have said? Would she not have taken her for a thief?

*

Madame Loisel came to know the ghastly life of abject poverty. Fromthe very first she played her part heroically. This fearful debtmust be paid off. She would pay it. The servant was dismissed. Theychanged their flat; they took a garret under the roof.

Shecame to know the heavy work of the house, the hateful duties of thekitchen. She washed the plates, wearing out her pink nails on thecoarse pottery and the bottoms of pans. She washed the dirty linen,the shirts and dish-cloths, and hung them out to dry on a string;every morning she took the dustbin down into the street and carriedup the water, stopping on each landing to get her breath. And, cladlike a poor woman, she went to the fruiterer, to the grocer, to thebutcher, a basket on her arm, haggling, insulted, fighting forevery wretched halfpenny of her money.

Everymonth notes had to be paid off, others renewed, time gained.

Herhusband worked in the evenings at putting straight a merchant'saccounts, and often at night he did copying at twopence-halfpenny apage.

Andthis life lasted ten years.

Atthe end of ten years everything was paid off, everything, theusurer's charges and the accumulation of superimposedinterest.

MadameLoisel looked old now. She had become like all the other strong,hard, coarse women of poor households. Her hair was badly done, herskirts were awry, her hands were red. She spoke in a shrill voice,and the water slopped all over the floor when she scrubbed it. Butsometimes, when her husband was at the office, she sat down by thewindow and thought of that evening long ago, of the ball at whichshe had been so beautiful and so much admired.

< 9 >

Whatwould have happened if she had never lost those jewels. Who knows?Who knows? How strange life is, how fickle! How little is needed toruin or to save!

OneSunday, as she had gone for a walk along the Champs-Elysees tofreshen herself after the labours of the week, she caught sightsuddenly of a woman who was taking a child out for a walk. It wasMadame Forestier, still young, still beautiful, stillattractive.

MadameLoisel was conscious of some emotion. Should she speak to her? Yes,certainly. And now that she had paid, she would tell her all. Whynot?

Shewent up to her.

"Goodmorning, Jeanne."

Theother did not recognise her, and was surprised at being thusfamiliarly addressed by a poor woman.

"But. . . Madame . . ." she stammered. "I don't know . . . you must bemaking a mistake."

"No. . . I am Mathilde Loisel."

Herfriend uttered a cry.

"Oh!. . . my poor Mathilde, how you have changed! . . ."

"Yes,I've had some hard times since I saw you last; and many sorrows . .. and all on your account."

"Onmy account! . . . How was that?"

"Youremember the diamond necklace you lent me for the ball at theMinistry?"

"Yes.Well?"

"Well,I lost it."

"Howcould you? Why, you brought it back."

"Ibrought you another one just like it. And for the last ten years wehave been paying for it. You realise it wasn't easy for us; we hadno money. . . . Well, it's paid for at last, and I'm gladindeed."

< 10 >

MadameForestier had halted.

"Yousay you bought a diamond necklace to replace mine?"

"Yes.You hadn't noticed it? They were very much alike."

Andshe smiled in proud and innocent happiness.

MadameForestier, deeply moved, took her two hands.

"Oh,my poor Mathilde! But mine was imitation. It was worth at the verymost five hundred francs! . . . "

爱华网

爱华网