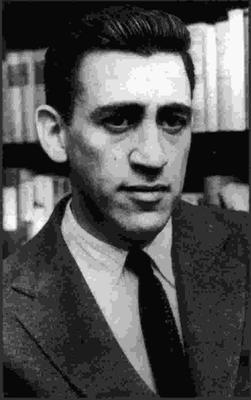

In Memoryof Mr. Jerome David Salinger

( 1919 - 2010 )

J·D·塞林格先生于今年一月廿七日与世长辞,《纽约客》杂志网站从档案库中整理出了所有塞林格先生在杂志上发表的作品,同时选取并刊登了不少悼念及回忆性文字。这篇文章正在其中,发表于2001年,时值《麦田里的守望者》(1951年)诞生五十周年。

HOLDEN AT FIFTY

写在霍尔顿诞生五十年之际

by LouisMenand

路易斯·梅南

October,12001

二〇〇一年十月一日

"The Catcher in the Rye" was turned downby The New Yorker. The magazine had published six of J. D.Salinger’s short stories, including two of the most popular, “APerfect Day for Bananafish,” in 1948, and “For Esmé—with Love andSqualor,” in 1950. But when the editors were shown the novel theydeclined to run an excerpt. They told Salinger that the precocityof the four Caulfield children was not believable, and that thewriting was showoffy—that it seemed designed to display theauthor’s cleverness rather than to present the story. “The Catcherin the Rye” had already been turned down by the publishing housethat solicited it, Harcourt Brace, when an executive there namedEugene Reynal achieved immortality the bad way by complaining thathe couldn’t figure out whether or not Holden Caulfield was supposedto be crazy. Salinger’s agent took the book to Little, Brown, wherethe editor, John Woodburn, was evidently prudent enough not to asksuch questions. It was published in July, 1951, and has so far soldmore than sixty million copies.

《麦田里的守望者》曾经被《纽约客》拒刊。杂志刊登过J·D·塞林格六部短篇小说,其中两部流传最广:一九四八年的《香蕉鱼的好日子》和一九五〇年的《献给爱斯美的故事——怀着爱与凄楚》。然而当编辑们看过《麦田里的守望者》后,却拒绝刊登节选。他们认为考尔菲德家四个孩子的少年老成让人难以置信,塞林格的文笔也过于炫耀,比起讲故事,更像抖聪明。而此时《麦田里的守望者》也早已被最初约稿的哈考特—布雷斯出版社退稿,当时社里的一位执行编辑尤金·雷纳尔抱怨说塞林格是不是疯了,他也因此恶名不朽。小布朗图书公司的编辑约翰·伍德布恩明显谨慎得多,塞林格的经理人拿书去的时候,他没有说出这种傻话。《麦田里的守望者》于一九五一年七月出版,至今已卖出六千万册。

The world is sad,Oscar Wilde said, because a puppet was once melancholy. He wasreferring to Hamlet, a character he thought had taught the world anew kind of unhappiness—the unhappiness of eternal disappointmentin life as it is, Weltschmerz. Whether Shakespeare invented it ornot, it has proved to be one of the most addictive of literaryemotions. Readers consume volumes of it, and then ask to meet theauthor. It has also proved to be one of the most enduring ofliterary emotions, since life manages to come up short prettyreliably. Each generation feels disappointed in its own way,though, and seems to require its own literature of disaffection.For many Americans who grew up in the nineteen-fifties, “TheCatcher in the Rye” is the purest extract of that mood. HoldenCaulfield is their sorrow king. Americans who grew up in laterdecades still read Salinger’s novel, but they have their ownversions of his story, with different flavors ofWeltschmerz—”Catcher in the Rye” rewrites, a literary genre all itsown.

奥斯卡·王尔德曾说过,世界因一个木偶的哀痛而悲伤。这木偶指的是哈姆雷特,在他看来,这个形象令世人领受了一种新的痛苦,一种对人生现实永远失望的痛苦,一种厌世情绪。且不论莎士比亚是否创造了它,这种痛苦逐渐变成文学之癖。读者成卷成帙买入这些作品,再求一见作者。这也是文学作品中最经久不衰的情绪,因为人生向来如此。尽管每一代人的失落不尽相同,人们都需要自己的文学,以泄愤懑。对于上世纪五十年代成长起来的美国人,《麦田里的守望者》正是这种情绪的提纯,霍尔顿·考尔菲德是他们的感伤之王。随后几代美国人也读塞林格的小说,不过对他的故事有自己的版本,有不同的厌世的味道。于是《麦田里的守望者》的故事被不断的重写,成为一个独立的文体。

In art, as in life,the rich get richer. People generally read “The Catcher in the Rye”when they are around fourteen years old, usually because the bookwas given or assigned to them by people—parents or teachers—whoread it when they were fourteen years old, because somebody gave orassigned it to them. The book keeps acquiring readers, in otherwords, not because kids keep discovering it but because grownupswho read it when they were kids keep getting kids to read it. Thisseems crucial to making sense of its popularity. “The Catcher inthe Rye” is a sympathetic portrait of a boy who refuses to besocialized which has become (among certain readers, anyway, for itis still occasionally banned in conservative school districts) astandard instrument of socialization. I was introduced to the bookby my parents, people who, if they had ever imagined that I might,after finishing the thing, run away from school, smoke like achimney, lie about my age in bars, solicit a prostitute, or use theword “goddam” in every third sentence, would (in the words of thestory) have had about two hemorrhages apiece. Somehow, they knewthis wouldn’t be the effect.

艺术有如人生,盛名者愈加丰盈。大部分人在十四岁左右接触到这部小说,或由父母推荐,或是老师布置,正是因为他们自己也在十四岁的时候读过这部小说。换言之,小说赢得了一代又一代读者,并非因为孩子们不断发现它,而是因为曾经读过它的孩子,长大成人后,继续让他们的孩子去读。这正是小说长盛不衰的关键原因。《麦田里的守望者》是一幅拒绝社会化的男孩的肖像,浸润着怜悯之情,同时它也是敦促孩子社会化的标准工具(至少对某些读者如此,因为一部分保守学区仍然抵制此书)。我的父母把我领进这本书。如果他们想到我看完以后,逃学,像烟囱一样吞云吐雾,谎报年龄混进酒吧,招妓,每三句话就有一个“他妈的”,(照书里的话来说)准会大发脾气。可不知为什么,他们觉得这并不会发生。

Supposedly, kidsrespond to “The Catcher in the Rye” because they recognizethemselves in the character of Holden Caulfield. Salinger isimagined to have given voice to what every adolescent, or, atleast, every sensitive, intelligent, middle-class adolescent,thinks but is too inhibited to say, which is that success is asham, and that successful people are mostly phonies. ReadingHolden’s story is supposed to be the literary equivalent of lookingin a mirror for the first time. This seems to underestimate theoriginality of the book. Fourteen-year-olds, even sensitive,intelligent, middle-class fourteen-year-olds, generally do notthink that success is a sham, and if they sometimes feel unhappy,or angry, or out of it, it’s not because they think most otherpeople are phonies. The whole emotional burden of adolescence isthat you don’t know why you feel unhappy, or angry, or outof it. The appeal of “The Catcher in the Rye,” what makes itaddictive, is that it provides you with a reason. It gives acontent to chemistry.

有种说法,孩子们之所以对《麦田里的守望者》深感共鸣,是因为他们在主人公霍尔顿·考尔菲德身上看到了自己。塞林格道出了每一个青春期孩子的心声,至少是每一个敏感、聪明、中产阶级家庭出身的少年的心声,他们的种种想法都被无情地禁止了:成功是可耻的,成功的大人都是骗子。阅读霍尔顿的故事就如同第一次照镜子,并将其用文学的笔法表现出来。这种说法似有低估小说原创性之嫌。十四岁的少年,就算是敏感、聪明、出身于中产阶级家庭,也不会认为成功是可耻的;他们有时不高兴了,生气了,自暴自弃了,也不是因为认为大人都是骗子。青春期的情感之所以沉重,是因为你根本不知道为什么自己会不高兴,会生气,会自暴自弃。《麦田里的守望者》的吸引力在于为你的提供了一种解释。它的快感在于满足了你的生理需要。

Holden talks like ateen-ager, and this makes it natural to assume that he thinks likea teen-ager as well. But like all the wise boys and girls inSalinger’s fiction—like Esmé and Teddy and the many brilliantGlasses—Holden thinks like an adult. No teen-ager (and very fewgrownups, for that matter) sees through other human beings asquickly, as clearly, or as unforgivingly as he does. Holden is ademon of verbal incision. He sums people up like anovelist:

霍尔顿少年般的谈吐让人自然而然的以为他的思想也像少年一样,不过如同塞林格笔下的所有聪明的男孩女孩——比如爱斯美,泰迪,以及格拉斯家族的孩子们——霍尔顿有着成人般的思维方式。没有哪个少年(甚至没有几个成年人)会像他那样得理不饶人,迅速而又清晰地洞悉世人。霍尔顿言辞犀利,鞭辟入里,简直就是个魔鬼。他像个小说家一样总结人性:

He was alwaysasking you to do him a big favor. You take a very handsome guy, ora guy that thinks he’s a real hot-shot, and they’re always askingyou to do them a big favor. Just because they’re crazy aboutthemselves, they think you’re crazy about them, too, andthat you’re just dying to do them a favor. It’s sort of funny, in away.

他老是要求别人大大帮他一个忙。有一种长得十分漂亮的家伙,或者一种自以为了不起的人物,他们老是要求别人大大帮他一个忙。他们因为疯狂地爱着自己,也就以为人人都疯狂地爱着他们,人人都渴望着替他们当差,说起来确实有点好笑。

She was blocking upthe whole goddam traffic in the aisle. You could tell sheliked to block up a lot of traffic. This waiter was waiting for herto move out of the way, but she didn’t even notice him. It wasfunny. You could tell the waiter didn’t like her much, you couldtell even the Navy guy didn’t like her much, even though he wasdating her. And I didn’t like her much. Nobody did. You hadto feel sort of sorry for her, in a way.

她把过道上整个儿的混账交通都堵塞住了。你看得出她很喜欢堵住交通。有个侍者等着她让路,可她甚至就当没有他这个人似的。真是好笑。你看得出那侍者并不喜欢她,你看得出甚至连那个海军也不喜欢她,虽说他把她约了出来。而我也不喜欢她。谁也不喜欢她。说来你倒真有点替她难受呢。

His name was Georgeor something—I don’t even remember—and he went to Andover. Big, bigdeal. You should’ve seen him when old Sally asked him how he likedthe play. He was the kind of a phony that have to give themselvesroom when they answer somebody’s question. He stepped back, andstepped right on the lady’s foot behind him. He probably brokeevery toe in her body. He said the play itself was no masterpiece,but that the Lunts, of course, were absolute angels. Angels. ForChrissake. Angels. That killed me.

他的名字叫乔治什么的——我都记不得了——是安多佛大学的学生。真——真了不起。可惜你没看见老萨莉问他喜不喜欢这戏时他那副样子。他正是那种假的不能在假的伪君子,回答别人问题的时候,还得给自己腾出地方来。他往后退了一步,正好一脚踩在一位站在他后面的太太的脚上。他大概把她那几个脚趾全都踩断了。他说那戏本身不怎么样,可是伦特夫妇,当然啦,完完全全是天仙下凡。天仙下凡。老天爷,天仙下凡。杀了我吧。”

"Youhad to feel sort of sorry for her, in a way.” The secret toHolden’s authority as a narrator is that he never lets anythingstand by itself. He always tells you what to think. He has everyonepegged. That’s why he’s so funny. But The New Yorker’seditors were right: Holden isn’t an ordinary teen-ager—he’s aprodigy. He seems (and this is why his character can be soaddictive) to have something that few people ever consistentlyattain: an attitude toward life.

“说来你倒真有点替她难受呢。”霍尔顿叙述起事情来颇为权威,他的秘诀是永远不让事实自己说话。他总要告诉你去想什么,把这些想法锲进读者脑中。这种做法多少有些幼稚可笑,但有一点《纽约客》的编辑们是说对了:霍尔顿并非普通少年,而是天才。他身上似乎(这也就是为什么这个角色如此吸引人)有种东西,绝少有人可以拥有,对人生的一种态度。

The moral of thebook can seem to be that Holden will outgrow his attitude, and thisis probably the lesson that most of the ninth-grade teachers whoassign “The Catcher in the Rye” hope to impart to theirstudents—that alienation is just a phase. But people don’t outgrowHolden’s attitude, or not completely, and they don’t want tooutgrow it, either, because it’s a fairly useful attitude to have.One goal of education is to teach people to want the rewards lifehas to offer, but another goal is to teach them a modest degree ofcontempt for those rewards, too. In American life, where—especiallyif you are a sensitive and intelligent member of the middleclass—the rewards are constantly being advertised as yours for thetaking, the feeling of disappointment is a lot more common than thefeeling of success, and if we didn’t learn how not to care ourfailures would destroy us. Giving “The Catcher in the Rye” to yourchildren is like giving them a layer of psychicinsulation.

《麦田里的守望者》的教育意义也许在于,霍尔顿最终会长大并离开那种精神状态。很多九年级教师布置学生们读这本书,正是希望书本可以传达给他们这一课——对社会的疏离只是成长的一个阶段。可也有人终其一生没有离开霍尔顿的这种精神状态,或多或少,他们也不想离开,因为这种态度还很有益处。教育的目标之一是教人们如何入世,另一目标则是教人们多少保有一点出世情怀。美国人的生活,特别是敏感、聪明的中产阶级的生活,经常被标榜为有付出就有回报,然而现实中,失意总多于得意,如果我们不学会排解失落,就只能自我毁灭。让孩子们读《麦田里的守望者》,就像他们的在心里罩上金钟罩,穿上铁布衫。

That it might endup on the syllabus for ninth-grade English was probably close tothe last thing Salinger had in mind when he wrote the book. Hewasn’t trying to expose the spiritual poverty of a conformistculture; he was writing a story about a boy whose little brotherhas died. Holden, after all, isn’t unhappy because he sees thatpeople are phonies; he sees that people are phonies because he isunhappy. What makes his view of other people so cutting and hisdisappointment so unappeasable is the same thing that makesHamlet’s feelings so cutting and unappeasable: his grief. Holden ismeant, it’s true, to be a kind of intuitive moral genius. (So,presumably, is Hamlet.) But his sense that everything is worthlessis just the normal feeling people have when someone they love dies.Life starts to seem a pathetically transparent attempt to trickthem into forgetting about death; they lose their taste forit.

塞林格写书的时候万万不会想到,《麦田里的守望者》最终会收进九年级的英语课本。他并非要揭露墨守成规的文化背后面临的精神贫乏。他只是想写一个故事,一个失去弟弟的男孩的故事。霍尔顿并不快乐,因为他觉得别人都是骗子。他觉得别人都是骗子,因为他并不快乐。他看人带着刻薄,内心满怀失落,这恰与哈姆雷特的刻薄与失落同出一处:他的悲伤。诚然,霍尔顿被世人本能地视为道德教化的天降之才(恰如哈姆雷特),但他那种万物虚无的感觉却与普通人并无二致。当人们痛失所爱,生活便成为一场骗局,拙劣又可怜,企图让你渐渐忘掉死亡。而人们受够了它。

What drew Salingerto this plot? Holden Caulfield first shows up in Salinger’s work in1941, in a story entitled “Slight Rebellion off Madison,” whichfeatures a character called Holden (he is not the narrator) and hisgirlfriend, Sally Hayes. (The story was bought by The NewYorker but not published until 1946.) And there are charactersnamed Holden Caulfield in other stories that Salinger produced inthe mid-forties. But most of “The Catcher in the Rye” was writtenafter the war, and although it seems odd to call Salinger a warwriter, both his biographers, Ian Hamilton and Paul Alexander,think that the war was what made Salinger Salinger, the experiencethat darkened his satire and put the sadness into hishumor.

塞林格是如何想出这样的情节的?霍尔顿·考尔菲德这个角色最早出现在塞林格一九四一年的作品《冲出麦迪逊的轻度反叛》中。作品塑造了霍尔顿(并非故事叙述者)和女朋友萨莉的形象。(《纽约客》买下了这个故事,但直到一九四六年才刊登出来)。霍尔顿·考尔菲德在塞林格四十五岁左右创作的其他故事中也出现过。然而《麦田里的守望者》的大部分内容写于战后。塞林格虽并不足以称为战地作家,但他的两位传记作者伊恩·汉密尔顿和保尔·亚历山大都认为,塞林格之所以为塞林格,正是战争让他的讽刺变得深沉,将感伤融入了他的幽默之中。

Salinger spent mostof the war with the 4th Infantry Division, where he was in acounter-intelligence unit. He landed at Utah Beach in the fifthhour of the D Day invasion, and ended up in the middle of some ofthe bloodiest fighting of the liberation—in Hürtgen Forest and thenin the Battle of the Bulge, in the winter of 1944. The 4th Divisionsuffered terrible casualties in those engagements, and Salinger, byhis own account, in letters he wrote at the time, was traumatized.He fought for eleven months during the advance on Berlin, and bythe summer of 1945, after the German surrender, he seems to havehad a nervous breakdown. He checked himself into an Army hospitalin Nuremberg. Shortly after he was released, and while he was stillin Europe, he wrote the first story narrated by Holden Caulfieldhimself, the real beginning of “The Catcher in the Rye.” It wascalled “I’m Crazy.” (It was published in Collier’s inDecember, 1945.)

战时的大部分时间,塞林格都在第四步兵师的反情报小组。诺曼底登陆那天,进攻发起五小时后,塞林格便从犹他海滩登陆。一九四四年冬,他参与了两场解放欧洲过程中最残酷的战斗,许特根森林战役和突出部战役。第四步兵师伤亡惨重,塞林格在当时的信件中曾说,他自己也受到了精神创伤。在进攻柏林时,他连续作战十一个月,以至于到一九四五年夏,德国投降后,塞林格一度精神崩溃,到部队医院住了一段时间。离开医院后不久,仍在欧洲逗留的他,写下了第一篇以霍尔顿·考尔菲德的口吻讲述的故事。这也就是《麦田里的守望者》的真正开始。这个故事题为《我疯了》(于一九四五年十二月在《柯利尔》杂志发表)。

"A Perfect Day forBananafish,” published a little more than two years later, is, ofcourse, the story that both introduced Seymour Glass, the oldestand most improbably gifted of the Glass children, and finished himoff, since Salinger has Seymour kill himself on the last page. Ifwe know Seymour only from the later stories in the Glass saga, inwhich he appears as a kind of saint—”Franny” and “Raise High theRoof Beam, Carpenters” (both published in The New Yorker in1955), “Zooey” (1957), “Seymour: An Introduction” (1959), and“Hapworth 16, 1924” (1965), Salinger’s last published work—we arelikely to assume that he killed himself because the world’sstupidity had made him crazy. But in “A Perfect Day for Bananafish”it is clear that Seymour kills himself because the war has made himcrazy. He has just been discharged from an Army hospital, and hisbehavior in the story isn’t saintly or visionary or engaginglyeccentric; it’s nutty and, in the end, psychotic. Seymour is a warcasualty. So, much more obviously, is the unnamed protagonist of“For Esmé—with Love and Squalor,” an American soldier who isbefriended by a thirteen-year-old English girl just before he goesoff to take part in the D Day invasion. “The Catcher in the Rye”was a best-seller when it came out, in 1951, but its reception assome sort of important cultural statement didn’t happen until themid-fifties, when people started talking about “alienation” and“conformity” and “the youth culture”—the time of “Howl” and “RebelWithout a Cause” and Elvis Presley’s first records. It is as a heroof that culture that Holden Caulfield has survived. But “TheCatcher in the Rye” is not a novel of the nineteen-fifties; it’s anovel of the nineteen-forties. And it is not a celebration ofyouth. It is a book about loss and a world gone wrong.

两年多后,塞林格发表了《香蕉鱼的好日子》,这个故事让我们结识了西摩·格拉斯,这个格拉斯家族中最大的孩子,也是最有才华的孩子。也就在这个故事里,塞林格安排西摩自杀,在小说的最后一页,结束了他的生命。在格拉斯家族的后续故事中,包括《弗拉尼》、《抬高房梁,木匠们》(两者均在1955年发表于《纽约客》)、《佐伊》(1957年)、《西摩:小传》(1959年)以及塞林格发表的最后一篇作品《哈普沃斯十六号,一九二四年》(1965年),西摩都以圣人的姿态出现。如果仅从这些故事来看,我们理所当然地会认为,西摩之死是因为世界的愚蠢让他疯狂而自杀,但是《香蕉鱼的好日子》交代得很清楚,西摩是因为战争让他疯狂而自杀。他刚从部队医院出来,在作品中,他的举止并不像圣人,也没有什么见识,更没有那些天才似的怪癖。他只是有些疯疯癫癫,直至最后精神错乱。西摩是战争的牺牲品,同样地,《献给爱斯美的故事——怀着爱与凄楚》中的无名主人公也是战争的牺牲品,而且表现得更明显。他是一个美国士兵,就在参加诺曼底登陆之前,与一个十三岁的英国女孩成为朋友。《麦田里的守望者》于一九五一年刚一问世就成为畅销书,但其作为重要文化宣言的地位并没有确立。直到五十年代中期,霍尔顿·考尔菲德才作为一个文化英雄生存下来。那时候,人们开始讨论“异化”、“从众行为”和“少年文化”等概念,《嚎叫》、《无因的反抗》的时代到来,猫王发行了第一张唱片。尽管如此,《麦田里的守望者》仍是一部四十年代的小说,而非五十年代。它不是对青春的欢庆,而是关乎一个充满迷惘的世界,一个走向错误的世界。

『譯聞·J·D·塞林格:文學與人生一 』

更多阅读

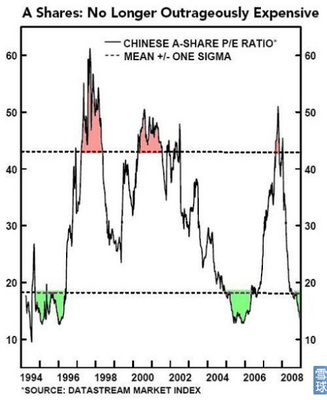

2013年格雷投资致客户的一封信 致客户的一封信

2013年格雷投资致客户的一封信致尊敬的格雷客户:2012年上证指数继续震荡走低,12月在金融股的强势带领下,勉强收阳,全年涨幅3.17%。深证成指全年涨幅2.22%,而中小板指数则是下跌1.38%,创业板指数下

我所知道的塞林格 塞林格是一个怎样的人

美国新罕布什尔州的西北角,有个小镇名叫科尼什,很优美,也很安静,2000年时曾有统计说,小镇上的居民一共就1661人。曾以《麦田里的守望者》轰动世界的著名作家JD·塞林格,自上世纪60年代开始就一直隐居在这个小镇上。50年来,派遣记者前往这

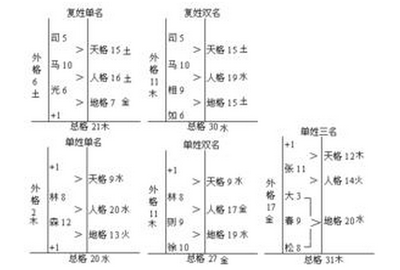

五格:天格、地格、人格、总格、外格

所谓五格剖象法就是根据《易经》的“象”“数”理论,依据姓名的笔画数和一定的规律建立起的五格数理关系,并运用阴阳五行相生相克的道理,推算人生各方面运势的一种简易方法。对于姓名学的内容,要用辩证的眼光去看,给后代、子女取名时不妨

唐朝新定詩格:唐·崔融

唐朝新定詩格 唐·崔融十體一形似體。二質氣體。三情理體。四直置體。五雕藻體。六映帶體。七飛動體。八婉轉體。九清切體。十菁華體。一、形似體。形似體者,謂貌其形而得其似可以妙求,難以粗測者是。詩云:〔風花無定影,露竹有餘清。〕

道林·格雷 Dorian Gray dorian gray 音乐剧

首页 小组 读书 电影 音乐 同城 九点 书籍电影音乐小组成员活动搜索 热评 排行榜 分类浏览 电视剧 你好,请 登录或 注册道林·格雷 Dorian Gray放在你的blog里!导演: Oliver Parker编剧: Oscar Wilde / Toby Finlay

爱华网

爱华网